How aggressive is method inlining in JVM?

public void processOnEndOfDay(Contract c) {

if (DateUtils.addDays(c.getCreated(), 7).before(new Date())) {

priorityHandling(c, OUTDATED_FEE);

notifyOutdated(c);

log.info("Outdated: {}", c);

} else {

if(sendNotifications) {

notifyPending(c);

}

log.debug("Pending {}", c);

}

}

First of all it has unreadable condition. Doesn't matter how it's implemented, what it does is what matters. So let's extract it first:public void processOnEndOfDay(Contract c) {

if (isOutdated(c)) {

priorityHandling(c, OUTDATED_FEE);

notifyOutdated(c);

log.info("Outdated: {}", c);

} else {

if(sendNotifications) {

notifyPending(c);

}

log.debug("Pending {}", c);

}

}

private boolean isOutdated(Contract c) {

return DateUtils.addDays(c.getCreated(), 7).before(new Date());

}

Apparently this method doesn't really belong here (F6 - move instance method):public void processOnEndOfDay(Contract c) {

if (c.isOutdated()) {

priorityHandling(c, OUTDATED_FEE);

notifyOutdated(c);

log.info("Outdated: {}", c);

} else {

if(sendNotifications) {

notifyPending(c);

}

log.debug("Pending {}", c);

}

}

Noticed the different? My IDE made isOutdated() an instance method of Contract, which sound right. But I'm still unhappy. There is too much happening in this method. One branch performs some business-related priorityHandling(), some system notification and logging. Other branch does conditional notification and logging. First let's move handling outdated contracts to a separate method:public void processOnEndOfDay(Contract c) {

if (c.isOutdated()) {

handleOutdated(c);

} else {

if(sendNotifications) {

notifyPending(c);

}

log.debug("Pending {}", c);

}

}

private void handleOutdated(Contract c) {

priorityHandling(c, OUTDATED_FEE);

notifyOutdated(c);

log.info("Outdated: {}", c);

}

One might say it's enough, but I see striking asymmetry between branches. handleOutdated() is very high-level while sending else branch is technical. Software should be easy to read, so don't mix different levels of abstraction next to each other. Now I'm happy:public void processOnEndOfDay(Contract c) {

if (c.isOutdated()) {

handleOutdated(c);

} else {

stillPending(c);

}

}

private void handleOutdated(Contract c) {

priorityHandling(c, OUTDATED_FEE);

notifyOutdated(c);

log.info("Outdated: {}", c);

}

private void stillPending(Contract c) {

if(sendNotifications) {

notifyPending(c);

}

log.debug("Pending {}", c);

}

This example was a bit contrived but actually I wanted to prove something different. Not that often these days, but there are still developers afraid of extracting methods believing it's slower at runtime. They fail to understand that JVM is a wonderful piece of software (it will probably outlast Java the language by far) that has many truly amazing runtime optimizations built-in. First of all shorter methods are easier to reason. The flow is more obvious, scope is shorter, side effects are better visible. With long methods JVM might simply give up. Second reason is even more important:

Method inlining

If JVM discovers some small method being executed over and over, it will simply replace each invocation of that method with its body. Take this as an example:private int add4(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4) {

return add2(x1, x2) + add2(x3, x4);

}

private int add2(int x1, int x2) {

return x1 + x2;

}

You might be almost sure that after some time JVM will get rid of add2() and translate your code into:private int add4(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4) {

return x1 + x2 + x3 + x4;

}

Important remark is that it's the JVM, not the compiler. javac is quite conservative when producing bytecode and leaves all that work onto the JVM. This design decision turned out to be brilliant:- JVM knows more about target environment, CPU, memory, architecture and can optimize more aggressively

- JVM can discover runtime characteristics of your code, e.g. which methods are executed most often, which virtual methods have only one implementation, etc.

.classcompiled using old Java will run faster on newer JVM. It's much more likely that you'll update Java rather then recompile your source code.

add128() takes 128 arguments (!) and calls add64() twice - with first and second half of arguments. add64() is similar, except that it calls add32() twice. I think you get the idea, in the end we land on add2() that does heavy lifting. Some numbers truncated to spare your eyes:public class ConcreteAdder {

public int add128(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, ... more ..., int x127, int x128) {

return add64(x1, x2, x3, x4, ... more ..., x63, x64) +

add64(x65, x66, x67, x68, ... more ..., x127, x128);

}

private int add64(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, ... more ..., int x63, int x64) {

return add32(x1, x2, x3, x4, ... more ..., x31, x32) +

add32(x33, x34, x35, x36, ... more ..., x63, x64);

}

private int add32(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, ... more ..., int x31, int x32) {

return add16(x1, x2, x3, x4, ... more ..., x15, x16) +

add16(x17, x18, x19, x20, ... more ..., x31, x32);

}

private int add16(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, ... more ..., int x15, int x16) {

return add8(x1, x2, x3, x4, x5, x6, x7, x8) + add8(x9, x10, x11, x12, x13, x14, x15, x16);

}

private int add8(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, int x5, int x6, int x7, int x8) {

return add4(x1, x2, x3, x4) + add4(x5, x6, x7, x8);

}

private int add4(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4) {

return add2(x1, x2) + add2(x3, x4);

}

private int add2(int x1, int x2) {

return x1 + x2;

}

}

It's not hard to observe that by calling add128() we make total of 127 method calls. A lot. For reference purposes here is a straightforward implementation:public class InlineAdder {

public int add128n(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, ... more ..., int x127, int x128) {

return x1 + x2 + x3 + x4 + ... more ... + x127 + x128;

}

}

Finally I also include an implementation that uses abstract methods and inheritance. 127 virtual calls are quite expensive. These methods require dynamic dispatch and thus are much more demanding as they cannot be inlined. Can't they?public abstract class Adder {

public abstract int add128(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, ... more ..., int x127, int x128);

public abstract int add64(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, ... more ..., int x63, int x64);

public abstract int add32(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, ... more ..., int x31, int x32);

public abstract int add16(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, ... more ..., int x15, int x16);

public abstract int add8(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, int x5, int x6, int x7, int x8);

public abstract int add4(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4);

public abstract int add2(int x1, int x2);

}

and an implementation:public class VirtualAdder extends Adder {

@Override

public int add128(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, ... more ..., int x128) {

return add64(x1, x2, x3, x4, ... more ..., x63, x64) +

add64(x65, x66, x67, x68, ... more ..., x127, x128);

}

@Override

public int add64(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, ... more ..., int x63, int x64) {

return add32(x1, x2, x3, x4, ... more ..., x31, x32) +

add32(x33, x34, x35, x36, ... more ..., x63, x64);

}

@Override

public int add32(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, ... more ..., int x32) {

return add16(x1, x2, x3, x4, ... more ..., x15, x16) +

add16(x17, x18, x19, x20, ... more ..., x31, x32);

}

@Override

public int add16(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, ... more ..., int x16) {

return add8(x1, x2, x3, x4, x5, x6, x7, x8) + add8(x9, x10, x11, x12, x13, x14, x15, x16);

}

@Override

public int add8(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4, int x5, int x6, int x7, int x8) {

return add4(x1, x2, x3, x4) + add4(x5, x6, x7, x8);

}

@Override

public int add4(int x1, int x2, int x3, int x4) {

return add2(x1, x2) + add2(x3, x4);

}

@Override

public int add2(int x1, int x2) {

return x1 + x2;

}

}

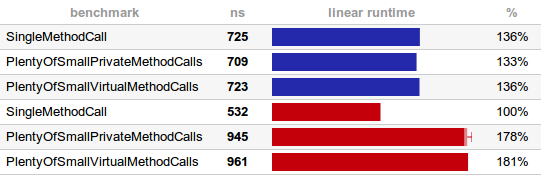

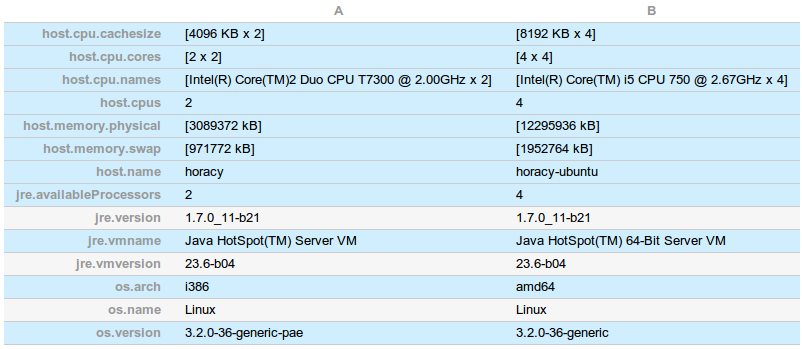

Encouraged by some interesting readers input after my article about @Cacheable overhead I wrote a quick benchmark to compare the overhead of over-extracted ConcreteAdder and VirtualAdder (to see virtual call overhead). Results are unexpected and a bit ambiguous. I run the same benchmark on two machines (blue and red), same software but the second one has more cores and is 64 bit:

Detailed environments:

It turns out that on a slower machine A JVM decided to inline everything. Not only simple

private calls but also the virtual once. How's that possible? Well, JVM discovered that there is only one subclass of Adder, thus only one possible version of each abstract method. If, at runtime, you load another subclass (or even more subclasses), you can expect to see performance drop as inlining is no longer possible. But keeping details aside, in this benchmark method calls aren't cheap, they are effectively free! Method calls (with their great documentation value improving readability) exist only in your source code and bytecode. At runtime they are completely eliminated (inlined).I don't quite understand the second benchmark though. It looks like the faster machine B indeed runs the reference

SingleMethodCall benchmark faster, but the others are slower, even compared to A. Perhaps it decided to postpone inlining? The difference is significant, but not really that huge. Again, just like with optimizing stack trace generation - if you start optimizing your code by manually inlining methods and thus making them much longer and complicated, you are solving the wrong problem.The benchmark is available on GitHub, together with article source. I encourage you to run it on your setup. Moreover each pull request is automatically built on Travis, so you can compare the results easily on the same environment. Tags: benchmarks, caliper, intellij idea, jvm